Aging is a complex biological process that dramatically influences health, particularly the risk of developing cancer. Intriguingly, while the likelihood of cancer increases significantly as we enter our 60s and 70s, research reveals a contrasting trend as we pass the age of 80—where risks start to decline. This article delves into recent findings regarding the interplay between age and cancer risk, focusing on the role of specific cellular mechanisms that could reshape our understanding of cancer treatment and prevention.

The initial increase in cancer risk as individuals age can be largely attributed to the accumulation of genetic mutations over decades. These mutations can affect cellular function, leading to rogue cell growth that characterizes cancer. However, this study highlights a crucial turning point, suggesting that beyond a certain age, perhaps due to the body’s changes and adaptive responses, the risk lowers. It raises critical questions about the mechanisms at play: Why does cancer risk decrease past a certain age, and what biological changes contribute to this phenomenon?

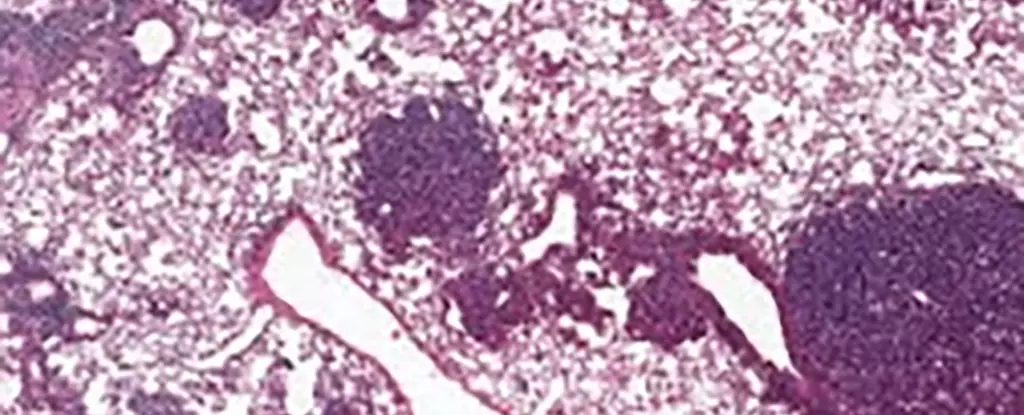

An international research team has conducted an in-depth analysis of lung cancer using mouse models, specifically focusing on alveolar type 2 (AT2) stem cells. These cells are not only essential for lung regeneration but are also often the starting point for many lung cancers. Their findings brought to light increased levels of a specific protein, NUPR1, in older mice. This protein appears to create a paradoxical effect where the aging cells behave as if they were iron-deficient, despite being iron-rich. According to cancer biologist Xueqian Zhuang from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, this anomaly leads to decreased regenerative capabilities in these cells, subsequently restraining both healthy cellular growth and tumor proliferation.

What’s particularly striking is that the same mechanisms observed in mice have also been detected in human cells. Elevated NUPR1 levels were correlated with a reduced availability of iron, compromising cell growth potential. The researchers discovered that by artificially lowering NUPR1 or increasing iron levels, the cell’s regenerative capacity improved. This avenue opens up exciting possibilities for cancer treatment, especially in older patients who may benefit from approaches targeting iron metabolism to enhance lung function or mitigate the effects of long-term conditions like COVID-19.

Another vital aspect raised by the study revolves around ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death linked to iron levels. Interestingly, older cells exhibited a reduced susceptibility to ferroptosis, making them potentially more resistant to certain cancer therapies based on this mechanism. The findings suggest that earlier intervention with ferroptosis-related treatments could provide better outcomes in younger patient populations, who may not yet exhibit the same cellular traits hindering effective treatment in older adults.

The implications of this research extend beyond treatment options; they underscore the importance of prevention strategies focusing on younger age groups. As Tuomas Tammela highlights, the risks associated with carcinogenic behaviors—such as smoking and excessive sun exposure—are even more critical than previously comprehended. Recognizing that cancer prevention efforts should prioritize youth could lead to a significant reduction in long-term cancer incidences.

The complexity of cancer biology interlinked with aging necessitates a deeply personalized approach to treatment. Factors such as cancer type, stage, and the patient’s overall health—including their age—must be evaluated to construct the most effective therapies. As our understanding of how aging affects cancer biology evolves, researchers are encouraged to further investigate the roles of proteins like NUPR1, potentially discovering new angles for treatment and prevention.

While the demographic shift towards an older population poses unique challenges regarding cancer risk, recent studies provide valuable insights that could significantly reshape our approach to cancer treatment and prevention. Understanding the nuances of aging in relation to cancer not only emphasizes the necessity for continued research but also the importance of tailored medical interventions, propelling the field toward more effective, individualized care.