The implications of antibiotic use for cognitive health have been a topic of considerable debate in medical communities. Recent research, notably a long-term study conducted within the ASPREE trial framework, has revealed intriguing insights, particularly concerning the demography of healthy older adults. While the study’s findings may contribute valuable knowledge to clinical practices, they also underscore the necessity for cautious interpretation and application of the results in broader elderly populations.

Understanding the Study Design and Population

The ASPREE trial, which originally focused on the effects of aspirin, recruited over 13,500 participants aged 70 years and older from the United States and Australia. This demographic was intentionally selected to exclude individuals with severe health complications, such as cardiovascular diseases or pre-existing dementia. Over a median period of 4.7 years, the researchers, led by Andrew Chan of Harvard Medical School, meticulously tracked antibiotic prescriptions and cognitive performance. The participants underwent cognitive assessments at baseline, one year into the study, and subsequently every two years, covering aspects like global cognitive function and memory.

Such a design provides a robust framework for analyzing the relationship between antibiotic use and cognitive outcomes. By focusing on an ostensibly healthy population, the study aimed to isolate the effects of antibiotic use without confounding factors that often obscure results in more varied cohorts. However, it also raises critical questions about the applicability of the findings to broader, multi-faceted elderly demographics who may face different health challenges.

One of the most significant revelations from the study is the clear lack of association between antibiotic usage and increased dementia risk among the cohort. Results indicated an HR of 1.03 (95% CI 0.84-1.25) for dementia and 1.02 (95% CI 0.94-1.11) for cognitive impairment without dementia when comparing antibiotic users to non-users. These findings suggest that, at least in healthy adults, antibiotics may not detrimentally impact cognitive health as previously theorized.

Previous studies had painted a more complex picture, with findings often contradicting each other. Some data from the Nurses’ Health Study II indicated that women with significant antibiotic exposure in midlife seemed to experience cognitive decline years later. Contrastingly, early trials hinted at a possibility that antibiotics could even mitigate cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s patients. The ASPREE findings create a new narrative, suggesting that for healthy older adults, antibiotic prescriptions may not have the feared long-term consequences for cognitive capabilities.

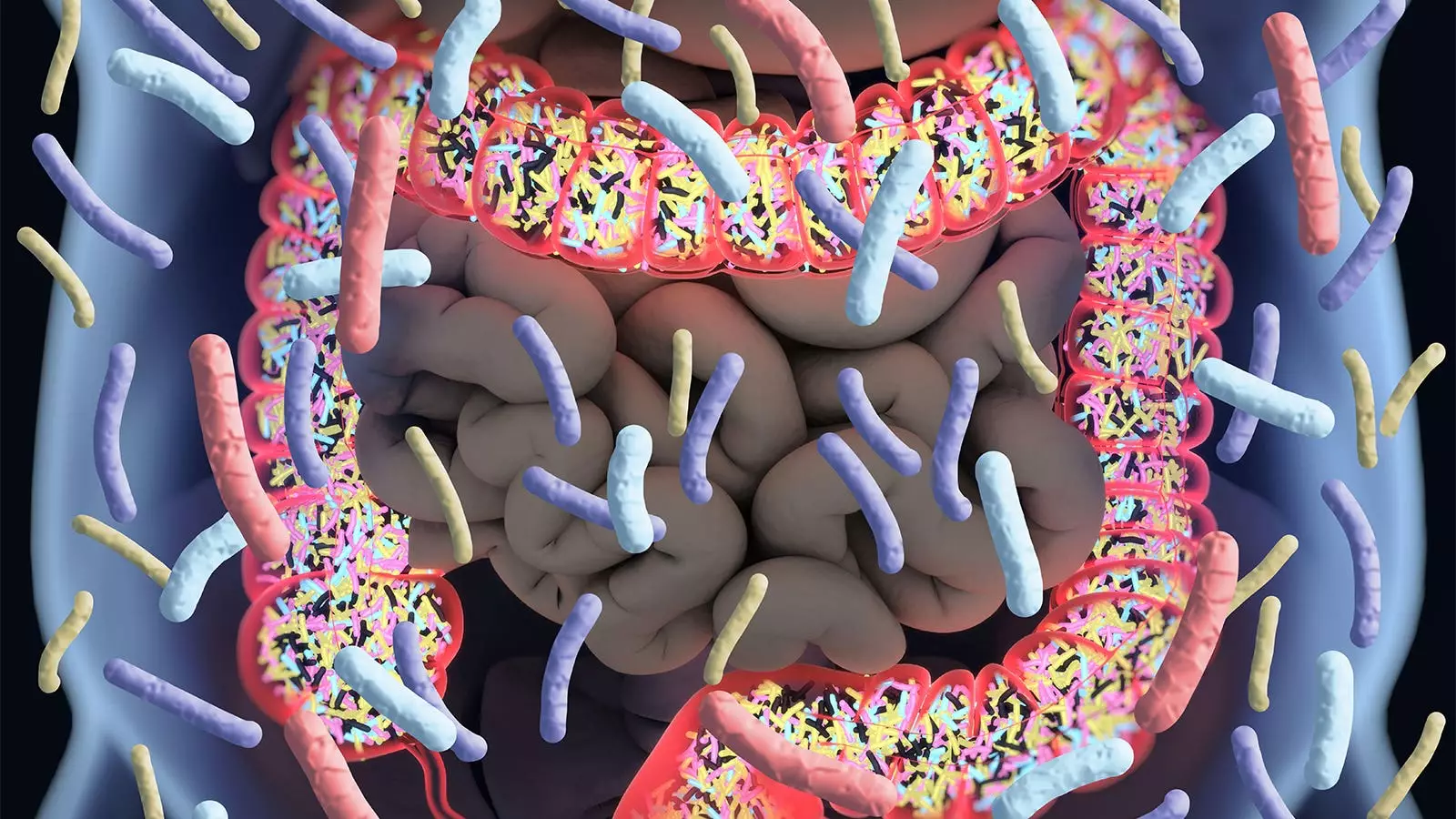

Despite this reassuring message, the relationship between gut health and cognitive function remains a focal point of discussion. Antibiotics are known to disrupt the gut microbiome, which has emerged as a critical player in maintaining overall health, including brain function. Andrew Chan emphasized the initial concerns regarding antibiotics’ potential to have adverse long-term effects on cognition, primarily due to their impact on gut health.

Furthermore, the study’s authors caution that while the results are promising, they are not without limitations. For instance, the study relied on filled prescription records to gauge antibiotic use, which may not accurately reflect actual consumption patterns. Issues of residual confounding cannot be ignored; varying underlying health conditions and lifestyle factors may yield differing results in broader populations not characterized by the stringent health criteria of this study.

The findings hold vital implications for healthcare practitioners who work with elderly populations, particularly regarding their prescribing practices. The results offer reassurance that, in a specific demographic of healthy older adults, the use of antibiotics does not appear to exacerbate cognitive decline. However, clinicians should remain vigilant and consider the broader implications when prescribing antibiotics to older patients who may have comorbid conditions.

Wenjie Cai and Alden Gross of Johns Hopkins University pointed out that there should be a cautious approach in interpreting these findings for clinical guidelines. They emphasized that the results may not apply universally to all elderly individuals, particularly those with complex health issues. Careful deliberation is warranted before integrating these findings into standard practices without further investigation.

As we advance our understanding of the intricate relationships between medical treatments and cognitive health, it becomes evident that further research is imperative. Although the ASPREE study has succeeded in providing clarity for a specific subset of older adults, the complexity of cognitive decline, combined with varying health profiles across the elderly population, calls for more comprehensive studies. It is essential to continue investigating how lifestyle, medication, and overall health collectively shape cognitive trajectories in older adults. The quest for clarity in the realm of cognitive health remains ongoing—a journey that requires patient-centered approaches and scientific rigor.