Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a critical lifesaving technique that can significantly improve the survival odds of a person experiencing cardiac arrest. When a heart stops beating, moments can mean the difference between life and death. Therefore, it’s alarming to discover that societal biases may hinder effective intervention in emergencies, particularly regarding gender. Recent findings from an Australian study revealed a disparity in CPR assistance provided by bystanders based on the patient’s gender, raising questions about the implications of traditional training methods.

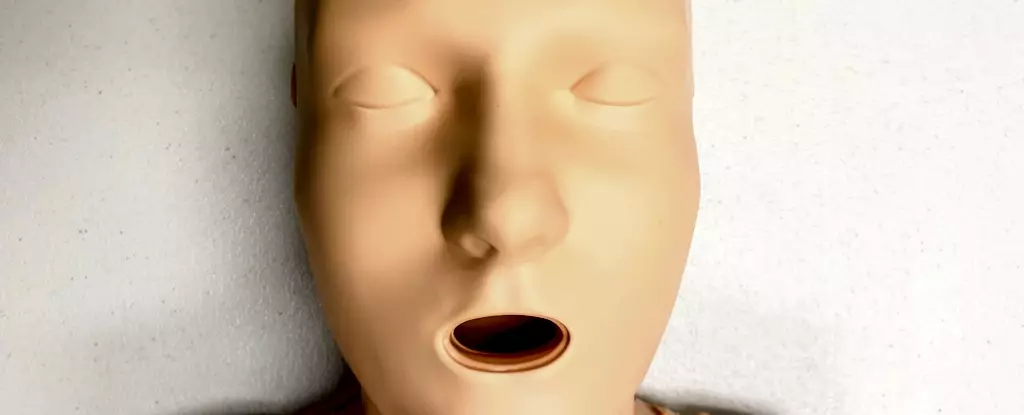

Statistics paint a concerning picture. Between 2017 and 2019, research indicated that bystanders were more inclined to administer CPR to men (74%) than to women (65%) during instances of cardiac arrest. This disparity may stem from a deeper societal issue — our training methods and resources reflect a predominantly male-centric approach. The majority of CPR training manikins, which are essential tools in teaching this life-saving skill, are notably flat-chested, with only a small fraction properly representing female anatomy. This lack of diversity in training aids may inadvertently communicate to trainees that only male bodies require intervention.

Furthermore, the urgency of the situation cannot be understated: Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death among women globally. Alarmingly, when women experience cardiac arrest outside of a hospital setting, they are 10% less likely to receive CPR compared to their male counterparts. This inaction can lead not just to death but also to severe, lifelong consequences, including brain damage.

The reluctance to perform CPR on women may arise from various cultural attitudes. Bystanders often hesitate due to concerns over being accused of inappropriate behavior or fears of causing harm due to preconceived notions about a woman’s fragility. Research indicates that these barriers manifest even in training environments; simulations have shown that participants often avoid removing a woman’s clothing in preparation for resuscitation, which can prove fatal if the situation requires urgent action.

Moreover, this behavioral inhibition has far-reaching implications. Studies suggest that the behaviors adopted during training scenarios closely mirror real-life emergency responses. If training curricula predominantly showcase male torsos, the likelihood of the trainees feeling prepared or confident to assist a woman when the need arises decreases drastically.

The Need for Diverse Training Manikins

An examination of the manikins available for CPR training highlights significant deficiencies in representation. In a recent analysis of the market, only 25% of 20 CPR manikins identified were designed to represent women, and notably, merely one had breasts. The overwhelming majority — a staggering 95% — were flat-chested, rendering the available training resources inadequate for instilling equal confidence across genders.

This not only emphasizes the need for inclusive training tools but also illustrates broader systemic issues at play. The existing training protocols lack attention to diversity in body types and skin tones. In a society where the perception of health risks can differ dramatically by gender and body characteristics, it is critical to cultivate a training environment that reflects diversity and equality.

Despite the discomfort that may accompany providing CPR to a woman, it is vital to prioritize life-saving measures over societal stigmas. The technique for performing CPR remains consistent regardless of gender; however, the readiness to act may very well hinge on the perception of preparedness that arises from training.

Recognizing the symptoms of a cardiac arrest—such as unresponsiveness and difficulty breathing—is crucial. When performing CPR, placing the heel of one hand on the chest’s center, interlocking fingers while keeping the arms straight, and compressing at a depth of approximately 5 cm are necessary steps. It is also essential to maintain a rhythmic pace of 100-120 compressions per minute. While participants needn’t worry about removing a woman’s bra in standard CPR maneuvers, understanding when to do so for life-saving measures like defibrillation is equally important.

Advocating for Change: Education and Awareness

There is an urgent need for enhanced education regarding cardiovascular health risks unique to women, as well as improved CPR training resources that are more representative. Diversifying CPR training materials to include woman-shaped manikins and other body types can not only empower bystanders to act decisively in emergency situations but also challenge antiquated notions regarding gender and frailty in health crises.

By reforming CPR training to become more inclusive and aware of gender dynamics, we take a significant step towards reducing disparity in emergency responses. It’s crucial that emergency preparedness training reflects the diversity of society. Lives depend on it—so let’s ensure that the training is as diverse as the population it aims to save.